Article wrote for oecd-development-matters.org by Andrea Vignolo, Executive Director of the Uruguayan Agency for International Cooperation, and Karen Van Rompaey, Knowledge Manager of the Uruguayan Agency for International Cooperation

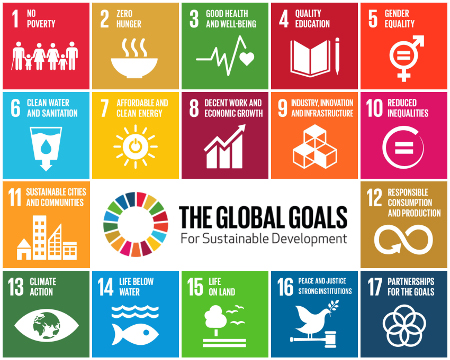

ODA’s eligibility and graduation criteria are still based fundamentally on countries’ economic growth performance. A growing consensus among academic, practitioner and political communities reveal that classifying countries according to their per capita income is inadequate to measure well-being or sustainability. Furthermore, it is not fit for the purpose of “leaving no one behind” in the era of universal sustainable development goals.

ODA’s eligibility and graduation criteria are still based fundamentally on countries’ economic growth performance. A growing consensus among academic, practitioner and political communities reveal that classifying countries according to their per capita income is inadequate to measure well-being or sustainability. Furthermore, it is not fit for the purpose of “leaving no one behind” in the era of universal sustainable development goals.

Achieving sustainable development is a far more complex enterprise than achieving economic growth. It requires not only the latter, but also specific knowledge, technologies, the right incentives and institutional capacities to change the way we currently live, work, produce, consume, share the fruits of growth and treat the planet. Otherwise, the quest towards economic growth can lead to negative consequences for the environment and future generations.

Middle- and upper-income developing countries have had access to an enhanced domestic resource base in the past decade to set forth their development priorities. They increasingly have assisted other developing countries through South-South and triangular co-operation. As a result of this growth in their aggregate income, some of them, like Antigua and Barbuda, Chile and Uruguay, have been classified recently as “high-income countries.”

Is this just good news?

Despite past growth and progress in their human development indicators, most of these upper-income developing countries still face acute structural gaps and vulnerabilities that constitute persistent development bottlenecks. They need to close gaps in policies, institutions and capacities to ensure policy coherence towards sustainable development. They lag behind when it comes to accessing, for example, technologies and knowledge, both of which are the “game changers” required to transform their current model of growth into sustainable development.

Moreover, the “rise of the South” has halted in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), threatening to jeopardize all progress made to date. Currently, the LAC region is experiencing a slowdown in trade, a decrease in investment in physical infrastructure as well as human capital and innovation, and a reduction in fiscal space. External vulnerability remains very high since most of the economies in the region lack diversification and are vulnerable to climate change.

Hence, ODA can play a strategic role to support these countries in the transition needed to build capacities in key areas/policy issues such as institutions, economic structures, risk management, social cohesion, research and innovation/technology to effectively achieve sustainable development.

Furthermore, by participating in triangular co-operation schemes, these developing countries can expand their contribution to global sustainable development by sharing their experiences, lessons learned and policy innovations.

Humankind stands at a critical juncture, when it is important to count on the contributions and support of all stakeholders to achieve the global sustainable development goals. It is therefore necessary to work towards an integral and non-exclusionary system of development co-operation that will fulfill the commitments made to date.

For an international co-operation system to be truly integral and non-exclusionary, it needs to provide the right incentives and overcome any zero-sum glance at the issues. While focusing on countries with greater challenges and less capacity to mobilise their own resources, ODA should support all developing countries according to their diverse conditions and needs. In this way, they can build their capacities and contribute towards global sustainable development.

Finally, it is thus necessary to review the OECD Development Assistance Committee’s current ODA graduation criteria to include other multidimensional measures of well-being and sustainability beyond GNI and an alternative timeframe, according to the scale of both the challenges and commitments of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development.

See related topics